AIR POLLUTION

Saturday, December 7, 2019

AIR POLLUTION THE BURNING ISSUE

let's start with someone

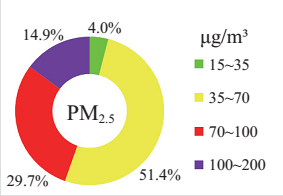

“I’VE never seen Beijing like this,” said Emmanuel Macron, the French president, beneath an unaccustomed cerulean sky at the end of a recent visit. The next day Greenpeace East Asia, an NGO, showed that his impression was accurate. It found that concentrations of PM 2.5—the smallest polluting particles, which pose the greatest health risks—were 54% lower in the Chinese capital during the fourth quarter of 2017 than during the same period of 2016. Concentrations of PM 2.5 in 26 cities across northern China, the province-sized metropoles of Beijing and Tianjin, were one third lower. China genuinely has reduced its notorious air pollution. How has it done it and at what cost?

The country has had draconian anti-pollution measures since 2013, when it introduced a set of prohibitions called the national action plan on air pollution. This imposed a nationwide cap on coal use, divided up among provinces, so that Beijing (for instance) had to reduce its coal consumption by 50% between 2013 and 2018. The plan banned new coal-burning capacity (though plants already in the works were allowed) and sped up the use of filters and scrubbers. These measures cut PM-2.5 levels in Beijing by more than a quarter between 2012-13, the time of the city’s notorious “airpocalypse”, and 2016. The measures were notable for being outright bans on polluting activities, rather than incentives to clean up production, such as prices or taxes (though China has those, too, including what will be the world’s largest carbon market, when it opens this year).

China started to seriously control air pollution from 2006 to 2010 by limiting emissions for each province. Relying on satellite data, my research shows that this first attempt was ultimately successful in reducing nationwide SO2 emissions by over 10 percent relative to 2005. Studying compliance over time, however, suggests that reductions in air pollution only happened after the Chinese government created the MEP in 2008. After its creation, among the many changes in environmental policy, the MEP started to gather reliable SO2 emissions data from continuous emissions monitoring systems (CEMS) at the prefecture level and increased the number of enforcement officials by 17 percent (a task that EDF China actively supported).

This early success notwithstanding, China could do better by implementing well-designed market-based solutions, policies that align with the country’s ambition to combine economic prosperity and environmental protection. Or, in the words of President Xi, to combine ‘green mountains and gold mountains’.

For example, a well-designed cap-and-trade program at the province level could have decreased the cost of air pollution abatement from 2006 to 2010 by 25% according to my research. The anticipated launch of a sectoral emissions trading system to limit a portion of China’s greenhouse gas emissions suggests that the Chinese government is looking to embrace lessons learned in air pollution control and wishes to build on its own pilot market-based pollution control programs to bring its environmental policy into the 21st century.

EDF is playing a key role in helping this endeavor through both hands-on policy work and research. The timing is serendipitous: China is at a cross-roads in environmental policy. Evidence based policy making is welcome. And data quality has improved in recent years. Given the right set of policies, countries can control air pollution, and improvements in air quality typically go hand in hand with economic prosperity.

Both China and London have remaining challenges. Despite dramatic improvements, Londoners, like the Chinese, still live with significant air pollution. A recent report on London’s air pollution found the city is not close to meeting WHO standards. Meeting them will be a challenge, in part because of the complexity of the causes (road transport accounts for over half of local contributions). So just as London must keep battling to improve air quality, Beijing will need to do likewise–but at least now each can now learn from the other.

PREVENTION

In the 1970s, China adopted a modern management of environmental problems, which was modeled on the approaches of the western world. Since the country’s participation in the Stockholm Conference on the Human Environment in 1972, the “management of the physical environment has evolved from a focus on eliminating existing pollution to preventing it all together [sic]" (He et al., 2012 :29).

8China’s PCAP is illustrative of this evolution which, according to Feng and Liao (in press), passed through three phases: beginning (1979-1999), development (2000-2013) and improvement (2014-present). The ‘beginning phase’ was characterized by efforts to situate PCAP in the legal system. Both the Environmental Protection Law of 1979 (trial version) and the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Law (1987) stipulated general provisions and guidelines for supervision and management. During the ‘development phase’, initiatives such as ‘Two Control Zones’, which involved “a region … affected by high sulfur dioxide (SO2) concentrations and/or acid rain, and a system to collect emission fees from all polluters” (Feng & Liao, in press: 5), attempted to move towards a more regulated and realistic regional approach. The ‘improvement phase’ (2014-present), represents a turn in the governance of air pollution, becoming strengthen after national episodes of high PM2.5 in 2013 (Feng & Liao, in press: 5). The most notorious initiative until now has been the amendment of the Environmental Protection Law 2015 (EPL), a decision which was postponed for years. According to Qin (2015) the new EPL introduced changes in “almost every major article, after passing through three separate hearings and doubling in length from its original version”. Although it is too soon to assess its effects on the overall PCAP, EPL is “perceived as the most progressive and stringent law in the history of environmental protection in China” (Zhang & Cao, 2015: 433).

9PCAP policy frameworks in China are constituted of laws, standards, regulations and action plans. Five-Year Plans (FYPs) are especially relevant for the definition of guidelines for economic and social policy, including environmental protection.

10Specifically regarding air pollution, some “FYPs mandate overall directions for the revision of laws, regulations, standards, and other measures and instruments for air pollution” (Lin & Elder, 2014: 15). Before the 12th FYP in 2012, some of the most crucial initiatives promulgated included: Prevention and Control of Atmospheric Pollution Law (1987, 1995, 2000), the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (GB3095-1996) and the Emission Standards of Air Pollutants for Thermal Power Plants (GB13223-2003) (Chan & Yao, 2008).

11In general terms, the execution of the policy framework is the responsibility of the Ministry of Environmental Protection (MEP) and the local Environmental Protection Bureaus (EPBs) in different jurisdictions. Other ministries and agencies (e.g., Ministry of Science and Technology) have specific roles when the policy incorporates varied aspects such as energy, industry, and technology.